Visiting the Temple — Basic Buddhism

1. Medicine Buddha

Medicine Buddha is known as Bhaisayaguru in Sanskrit. In The Medicine Buddha Sutra describes the meritorious virtues of Medicine Buddha’s Eastern Pure Land of Azure Radiance.

The sphere of influence a Buddha presides over is determined by the vows the Buddha has taken while he is still a bodhisattva. Twelve vows were generated and practiced by the Medicine Buddha while he was still a bodhisattva. The first, second, third, and fourth vows are meant to bestow all sentient beings with joy. The fifth through twelfth vows can be generalized as those concerning the elimination of suffering in its multiple facets. What kind of Pure Land was a bodhisattva eventually able to fashion through the strength of those vows?

The Pure Land of the Medicine Buddha is described as a pristine land of crystal radiance, a world of abundance. All sentient beings in this land of affluence have no economic worries because there are abundant resources. The accessibility of food, clothing, housing, and transportation is of great convenience, and entertainment is available according to one's wishes.

The Pure Land of the Medicine Buddha is a society where all of its members remain uncorrupted, with no social problems such as fighting, killing, or addictions of any kind. In this Pure Land, every sentient being is physically and mentally healthy and enjoys life abundantly. Not only do sentient beings not suffer from any illness, they also do not experience any anxiety or frustration due to greed, anger, and jealously. The sentient beings in this Pure Land usually aid others in seeking liberation.

By practcing the Medicine Buddha teachings, all sentient beings can receive four particularly beneficial outcomes: longevity, wealth, high occupational positions, and male or female offspring according to the parents' wishes. Moreover, the arising of various strange phenomena as well, as all varieties of fear, will subside. All calamities due to warfare, declining morality, all forms of violation, and the risks associated with childbirth will be eliminated. Medicine Buddha emphasizes releasing sentient beings’ suffering and bestowing joy in this present life, to serve as a precious Dharma solution for the practical issues in life.

2. Sakyamuni Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, the historical founder of Buddhism, was an Indian prince of the Sakya clan.He was born around 500 BCE in the kingdom of Kapilavastu (present-day southern Nepal). After his awakening, he was known as Sakyamuni, “sage of the Sakyans.”

The prince was named Siddhartha, which means “accomplishing all.” As was the custom, his father, King Suddhodana, summoned the most learned of wise men to foretell his son’s destiny. One of the prince’s first visitors was a renowned sage named Asita who predicted that Siddhartha would become a great king of the world if he remained a layperson, or he would become a Buddha who liberates sentient beings if he left the home life.

From an early age, it was quite evident that the young prince was extremely bright and that he excelled in all things. By the time Siddhartha was twelve years old, he was adept at the classical “five sciences” of composition, mathematics, medicine, logic, and philosophy and excelled at the study of the four Vedas. In addition to his abilities in a wide range of scholarly subjects, he was also an adept warrior who was skilled in the martial arts. The prince grew into a young man who was greatly admired for his strength, intelligence, dignity, and beauty.

When Siddhartha reached marrying age, King Suddhodana arranged for his son to take a wife. Yasodhara, the beautiful daughter of a Sakya nobleman, was chosen. Still, King Suddhodana feared that Prince Siddhartha might leave the palace and his royal position. To prevent his son from leaving, King Suddhodana sheltered him from the world by building him special pleasure palaces and surrounding him with beautiful women, music, wine, and other luxuries. Nevertheless, these worldly pleasures of the palace could not satisfy the feelings of loneliness that had crept into the prince’s heart.

One day, Siddhartha went to tell his father that he wished to travel outside the palace walls to see the kingdom. Hearing this, King Suddhodana immediately ordered that the kingdom be decorated and cleared of anything unpleasant. Furthermore, the elderly, the sick, the ascetics, and corpses were not permitted near the prince lest they arouse feelings that disturbed his mind. On his journeys, the prince and Chandaka, his personal charioteer, saw a frail-looking man who was bent over with age. Siddhartha, shocked by the sight, discovered that old age was a part of the human condition; he encountered a man who was extremely sick and knew that all people fall ill at some point in their lives; they driving in the chariot, they came upon a funeral procession, he watched as grief-stricken relatives carried a lifeless body through the streets, and he wished to know why people had to die.

Siddhartha then contemplated all that he had seen and lamented the realization that life was impermanent. On his final journey, Siddhartha and Chandaka encountered an ascetic who walked toward them. The man explained that he had renounced the world to seek liberation from the sufferings of old age, sickness, and death. After Siddhartha heard these words, his heart filled with joy, and his mind gave rise to the thought of taking up the life of a wandering ascetic. These visions beyond his life of contentment left an indelible impression on Siddhartha. His father noticed the change in him and desperately tried to divert him with more music, beautiful women, feasts, and fine things.

However, Siddhartha could not be deterred from his resolve to leave worldly life behind. In the prince’s twenty-ninth year of life, his wife bore him a son, Rahula. Not long afterward, the prince decided to leave the palace to seek liberation from old age, sickness, and death. As everyone slept, he rode away from Kapilavastu with faithful Chandaka by his side. When they reached a serene forest outside the city, the prince took off his fine silken clothing, removed his jeweled ornaments, cut off his long hair, and severed all attachments to his old life.

For the next six years, Siddhartha—who now went by his family name, Gautama—sought out teachers to learn how to be free from old age, sickness, and death. Since he had entered the life of an ascetic, Gautama followed the practices of fasting and meditating under extreme conditions of hardship and deprivation. After six years, he abandoned asceticism. From there, he made his way to Nairanjana and then traveled to Bodhgaya, where he seated himself beneath a tree that would later be known as the “bodhi tree” and began to meditate. He swore that he would not stir from his seat, even at the cost of his life, until he had liberated himself from the cycle of birth and death and attained awakening.

Sitting in meditation, Gautama conquered the demons of his mind—greed, anger, and ignorance—as well as Mara, the king of the demons. After defeating Mara, Gautama entered a deep meditative state called samadhi. Through this deep contemplation, he first saw all of his countless past lives. Then, he realized the non-duality of birth and death. He saw sentient beings within the six realms of existence suffering endlessly from karmic cause and effect. In the third realization, he came to understand dependent origination. Even after he realized the truth of the universe, Gautama continued to meditate and contemplate under the bodhi tree for twenty-one days. At the first light of dawn, Gautama finally awakened to the root of suffering—ignorance. Thus, he found the way leading to the cessation of this suffering. Forty-nine days after he had made his vow, on the eighth day of the twelfth lunar month, under a night sky filled with stars, Gautama attained complete awakening. He was thirty-five years old. From this moment forth, he was known as Sakyamuni Buddha.

After his awakening, the Buddha spent forty-nine years teaching the Dharma. Among his followers, there were former leaders of other religious traditions, kings and queens, rich and poor, men and women, and people from all walks of life. With great compassion and wisdom, he taught for the remainder of his life. At the age of eighty, on the fifteenth day of the second lunar month, under a pair of sala trees, the Buddha entered final nirvana.

The legacy he left his disciples was profound, for the Buddha had dedicated his earthly life to teaching others the Four Noble Truths, dependent origination, karma, the three Dharma seals, emptiness, the Noble Eightfold Path, the five precepts, the six perfections, and the Middle Way. Ever since Sakyamuni Buddha transmitted the Dharma to his disciples, countless sentient beings through the centuries have heard the teachings, cultivated the path, and attained awakening.

3. Buddha

The Sanskrit word Buddha means “awakened one,” and refers to those who have awakened to the Dharma, the truth. A Buddha does not only refer to the historical figure. Any human being who is totally dedicated to serving others and completes the path to full awakening can become a Buddha; after all, Sakyamuni Buddha was a teacher, not a god. As Buddhism spread throughout India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Central and East Asia, other Buddhas became part of the religion.

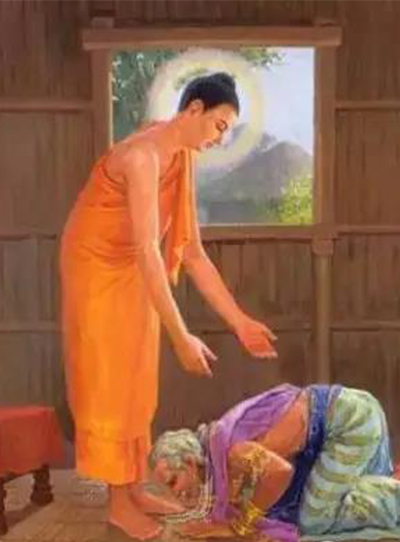

4. Bowing before the Buddha

What is the meaning of bowing? All Westerners are familiar with bowing. We have seen it in numerous movies and TV shows when the story originates in the Orient. We also have become used to seeing Asian government officials on the news bowing to one another and visitors to their countries. Further, as the West becomes more open to the culture, customs, and religions of the East, we often see people–clergy and laypersons–bowing to others. We know it is a form of respect and greeting. (Ina Denton)

To show respect to the Buddha for teaching the path to awakening, Buddhists often bow and or prostrate before Buddha images.

These gestures are not an act of worship but a way to develop humility, as well as to recognize our own potential to become awakened. Prostrating is also called “touching the Earth” because it humbles individuals and serves as a reminder that we are part of the Earth and a greater lineage. (Visiting a Buddhist Temple)

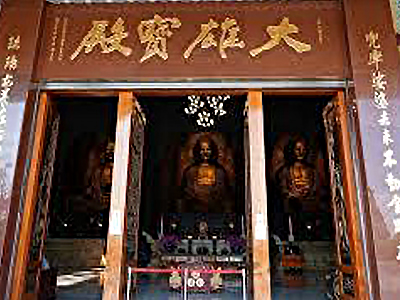

5. The Main Shrine

The Main Shrine, or Buddha Hall, is called the “Treasure Hall of the Great Hero,” and all temples, regardless of their size, will have a Main Shrine because it is the area where monastics perform services and practitioners chant sutras or offer reverence to the Buddha. The different images inside the hall may vary: Some Main Shrine depict just Sakyamuni Buddha, whereas others also include the Medicine Buddha and Amitabha Buddha. The Main Shrine might also have a depiction of the eighteen arhats or other Buddhist figures. The environment of the Main Shrine is maintained to have a dignified and tranquil atmosphere so individuals entering the hall feel a sense of admiration and devotion.

As the sacred center of the community, certain rules of etiquette apply in the Main Shrine.

Since the Buddha is the center of the religion, it is customary for Buddhist practitioners to visit the Main Shrine before any other part of the temple. Before entering, you should cover your shoulders and legs, and check to see if shoes should be removed and if photography is permitted. Show respect by removing hats, silencing phones, and keeping voices low. Eating and showing the bottoms of the feet towards Buddha or bodhisattva images is also considered impolite. Visitors should sit with feet flat on the floor or in a cross-legged meditation posture. (Adapted from FaXiang, published by FGSITC)

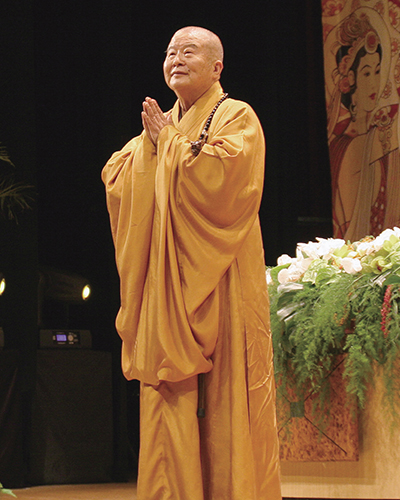

6. Monastic

Monastics can simply be addressed as “Venerable.” You can easily identify monastics by their shaved heads and long, ochre colored robes. Upon becoming ordained, monastics take many vows, including one to regularly shave their heads. According to the life story of the Buddha, upon departing his home to search for the end of suffering, one of the first things he did was shave his hair and exchange his ornate clothes for a simple robe; Buddhist monastics continue these practices to show their dedication to the Buddha’s path. Traditionally, robes were dyed to a saffron or ochre color from vegetable matter like roots and leaves. Often, a red clay was added to give the robe a slightly orange hue. Although vegetable dyes are rarely used today, the color was influential, and most traditions of Buddhism still use shades of color between red and brown for their robes.(Adapted from FaXiang, published by FGSITC)

7. Greeting

Joining palms and saying the Buddha’s name is how Buddhists express truth and goodness towards each other.

Many Buddhists greet each other with their hands joined together and placed at the center of the chest. This gesture symbolizes the lotus flower bud. The beautiful lotus flower grows out of the bottom of a pond, which is full of mud and decay. Because of their origin, lotus flowers are a symbol for awakening since a human being, although born in a world of pain and suffering, has the potential to go beyond and attain liberation. Lotus flowers can be found throughout temples. As a way to say hello, goodbye, or thank you, Buddhists often join palms and say, “Amituofo.” Amituofo is the Chinese pronunciation of Amitabha Buddha, meaning infinite life and infinite light. (Adapted from FaXiang, published by FGSITC)

8. Mountain Gate

There is a saying in Buddhism, that “Wealth enters the mountain gate and merit is credited to the generous benefactor.” The term “mountain gate” refers to the main entrance of a Buddhist temple, since many temples were once built in mountain forests.

The mountain gate represents a transition from the ordinary to the sagely, from ignorance to awakening, and from darkness to the light, symbolizing the entrance of the worldly into the Buddhist sphere. So they do not return empty handed, those who enter the mountain gate must leave their habitual tendencies at the door.

The mountain gate is also sometimes called the “triple gate,” as it represents the gate of faith, the gate of wisdom, and the gate of compassion. The gate of faith is entered by means of the Buddha, the gate of wisdom is entered by means of the Dharma, and the gate of compassion is entered by means of the Sangha. This is what it means to enter the Way by the Triple Gem. (Adapted from FaXiang, published by FGSITC)

9. Temple

A Buddhist temple forever remains the center of faith and a source of strength. A temple is a gathering place for good Dharma friends on the path together, a place to refuel on the road of life, and a vacation retreat for cultivating one’s spirit. It is a place of purity where we can wash away our affliction, bring ourselves close to the Dharma, and learn about compassion, wisdom, vows, and practice.

What's New?

DECEMBER

Humble Table, Wise Fare

INSPIRATION

Recorded by Leann Moore

Being humble before people,

the road is open wherever you go;

being arrogant before people,

it is difficult to move even one step.

Dharma Instruments

Venerable Master Hsing Yun grants voices to the objects of daily monastic life to tell their stories in this collection of first-person narratives.

Sutras Chanting

The Medicine Buddha SutraMedicine Buddha, the Buddha of healing in Chinese Buddhism, is believed to cure all suffering (both physical and mental) of sentient beings. The Medicine Buddha Sutra is commonly chanted and recited in Buddhist monasteries, and the Medicine Buddha’s twelve great vows are widely praised.

Newsletter

What is happening at Hsingyun.org this month? Send us your email, and we will make sure you never miss a thing!